Error 404

No amount of coaching is going to bring this page back!

We're not quite sure what went wrong, but we would love to help you find what you are looking for. Send us a message using the form below, or head on over to our website and read about our programs.

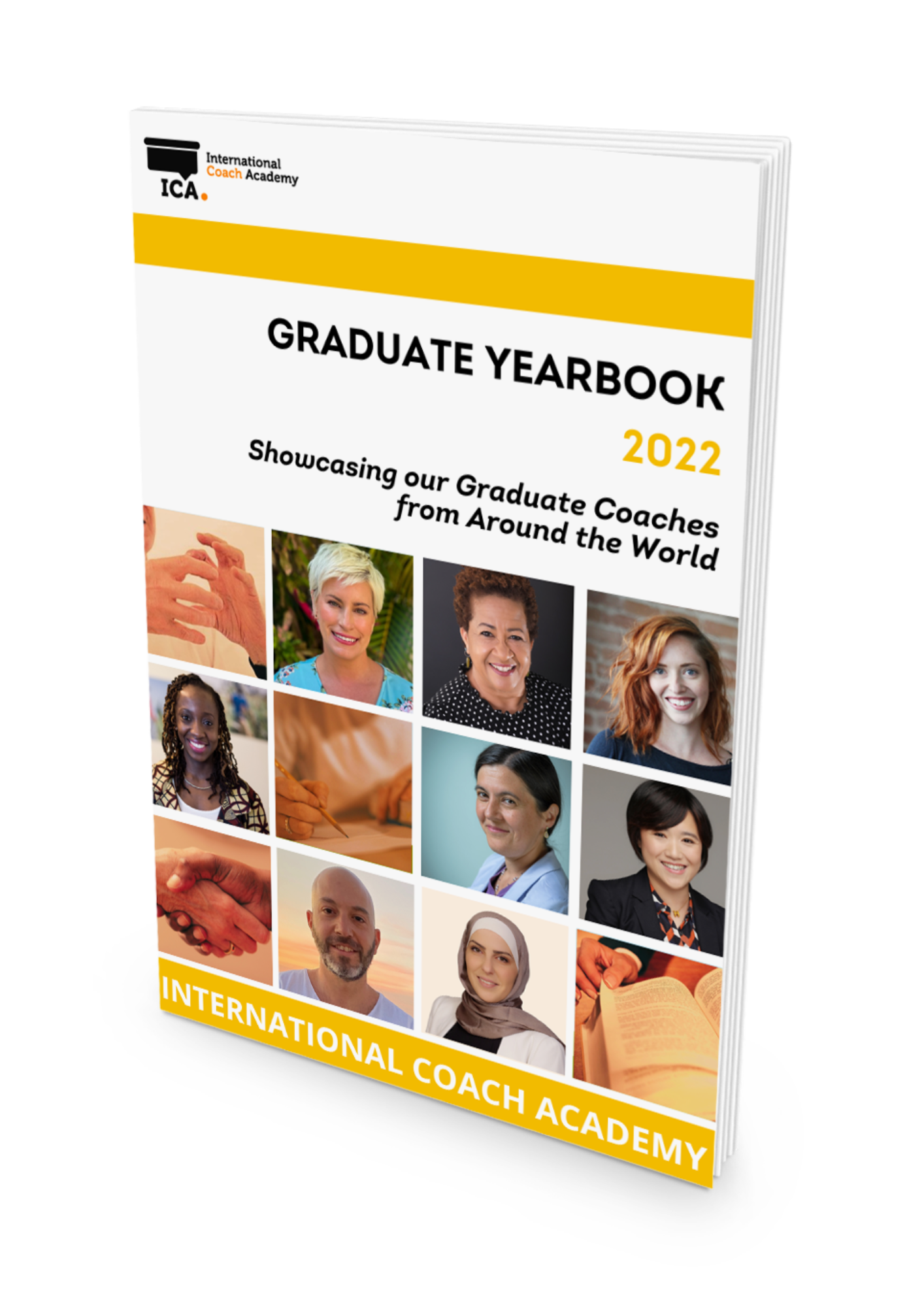

Meet Our Graduates

View Our 2022 Graduate Yearbook

The ICA Graduate Yearbook is not only a great showcase for our ICA Coaches, it is an excellent way to get a feel for our coaching community. Every ICA Coach develops their own unique niche and coaching model during their studies. This means they walk away with a Coaching Portfolio that is entirely their own IP. Our coaches tell us they use this all the time with new and current clients. It helps them communicate what they do in a clear and simple way. So make sure you click through and check out the Coaching Portfolios of our amazing 2022 graduates.

(No form required)

What Our Students Say

The great friendships made along the way. My peers were the greatest support in a season of upheaval with the pandemic, unemployment and the feeling of loss of community, it was the coaches that created a place where I felt part of something bigger. I loved working with coaches from all around the world.

Shawn Harvey Life Coach, CANADA

Learning with ICA allowed me to become the person I always wanted to be. Making the decision to leave a successful leadership career to become a coach was a very daunting one, but with ICA I felt right at home from the start and felt that for the first time I "fitted". I would like to thank the amazing team of people at ICA.

MARIA ISABEL VALLE RIVERA Executive and Expat Coach, BRUNEI

Many 'failed' coaching sessions had to happen until I really learned the difference between coaching the situation v.s. coaching the client. The difference is subtle but hugely powerful. This single piece of learning significantly changed the course of how I coach, and I hope now benefits my clients too.

SARAH JEFFERIES Transformational Coach, UNITED KINGDOM

What Sort Of Coach Will You Be?

The one thing that all coaches have in common is that they feel a natural talent or desire to create positive change in their lives, or the lives of others. But, within this profession there's many different niches and applications. Take our quick quiz to find out what sort of coach you will be.